Peter Sellars is an American theater and opera director as well as a distinguished professor at UCLA. His tremendously popular undergraduate course, “Art as Social Action,” insists on the power of art to create structures of equality. Sellars has served as Director of the Boston Shakespeare Company and the American National Theater in Washington D.C., Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Festival, and was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1983 for his innovative contributions to theater. He is known for his transformative interpretations of classic plays and operas, which were not always well-received by performance purists: His 1980 staging of Mozart’s Don Giovanni was deemed “artistic vandalism.” But art, Sellars unapologetically maintains, cannot be contained within the time period from which it originated, or relegated to its proper century; the arts, Sellars believes, “were invented to encourage long-term thinking.” The true power of art, and the task of the artist, is to create shared spaces—across divides in time and ideology—that provide us with new ways to think and be together.

The following interview with Sellars is a component of my senior seminar project, entitled “Othello Revisited: Repurposing the Western Literary Canon in Toni Morrison’s Desdemona.” Directed by Sellars, Morrison’s Desdemona is a creative retelling of Shakespeare’s Othello. Morrison’s play reflects upon the events of Shakespeare’s version from Desdemona’s perspective, specifically interrogating Desdemona’s relationships with Othello, Emilia and Barbary in order to explore their racial, class and gender power imbalances. The play originated out of a “creative pact” between Sellars and Morrison. Sellars “disliked the play Othello “intensely” due to what he saw to be its “zones of racial blindness,” and Morrison wanted to prove to him that Othello was still worth reading today. In Desdemona, Morrison expands upon hints, nuances and subtexts that Shakespeare had raised but failed to fully explore. She creates what Sellars terms a “structure of sharing,” allowing the characters to recognize and empathize with each other across deep divides. Within the timeless space of Desdemona, a kind of afterlife setting beyond life and death, Shakespeare’s characters have all of eternity to speak, listen, reflect and to understand each other better.

I spoke to Peter Sellars by Zoom on March 23, 2021 about his collaboration with Morrison, the lure of the afterlife, and the transformative power of theater to develop a collective conscience.

Maddie Turner: How did gender come to be such an important topic in Desdemona?

Peter Sellars: Toni was never moved by Othello in all the versions of it she saw. Her answer was not to reorient the play racially, but rather to reorient the play in terms of gender. Toni focused on all the women who died horribly in that play, and the women’s complicity in a system they didn’t dare challenge, which is all really shocking information for a brilliant, well-meaning, liberal Desdemona. So, Toni’s point is not just that race cannot speak its mind, but of course gender, too.

Shakespeare’s ideal woman says nothing, which is why, even as she’s being murdered, Desdemona has just about nothing to say. And so, Toni made an entire play about how silences are the sign and record of violence. Silence is not acquiescence: It is the trace of violence. Toni goes to the other side of silence, which is (to) the dead, who can finally speak and ask themselves why they didn’t speak when they were alive. They can see the cost of their silence, their complicity, their own deep resentments. And, meanwhile, Desdemona, who is this perfect figure of enlightenment—and Toni really does this amazing critique of enlightenment—like yes, you’re quite enlightened, and guess what, you’re clueless. Toni unfolds all of this across a very intense meditation that I think she perfected in Beloved: That the dead are anything but silent, and that the actual reckoning doesn’t often happen in this world, but what does happen in this world is actually shaped by the dead as much as by the living.

From what I’ve read and gleaned from clips, I’ve seen that Desdemona, Emilia and Othello are all voiced by one actress, is that correct? And Rokia Traoré plays Barbary, but is she the only other actress who has a speaking part on the stage?

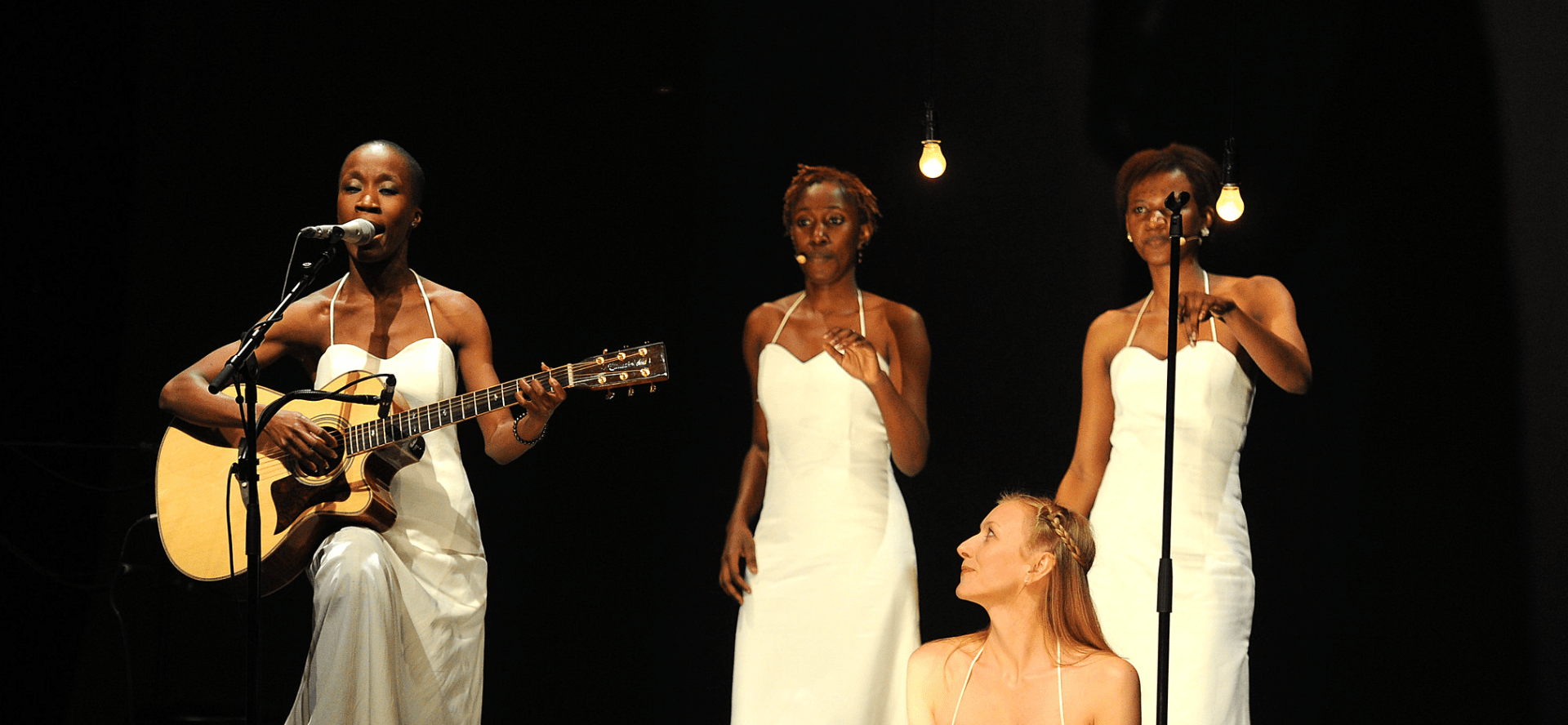

Yes, completely. And Rokia is also singing her own songs, which are really heart-rending and in deep waters of complex, emotional feeling. One of the things that really interested me was to have a collaborator who could speak from an African voice, and specifically a contemporary African voice, because Rokia is very much a contemporary woman in a new Africa. She’s trained in the Griot tradition, which was the way in which stories were told in Shakespeare’s lifetime in Africa. If Othello had been told in Africa, it would have been told with a kora and someone singing. And Rokia is trained in that tradition, so there was both a historical and a contemporary authenticity. Toni could be in direct contact with Rokia and Rokia could be in direct contact with Toni, and two women on opposite sides of the Atlantic with opposite connections to these histories could compare notes. So, that exchange is always alive in the theater space—of Rokia engaging Toni, and Toni engaging Rokia. The theatrical part of it is, first of all, music as a way of storytelling, but also music in the sense of the epic—the traditional epics of Africa and of Greece, which were sung. Singing is such a big deal in mythic storytelling because it opens other emotional spaces, and also creates intensity and a commitment. There’s no place to hide. Music goes inside, inside, inside, inside and touches things that even words can’t touch. And, also, this hypnotic space of African music, which never begins and never ends. These songs flow across time and space.

I love the idea that the play takes place in this “afterlife” of liminal space. The original play is so rushed. Othello and Desdemona elope and three days later, everything has just gone completely wrong. But in this space where there’s finally all the time in the world, there’s no reason not to have these conversations.

Oh, absolutely. That whole question of, you have eternity, when do you want to get real? It’s incredible. And Toni also was in a very quiet, contemplative time in her life. She wasn’t a young provocateur; she was deeply invested in the long view. And so, this play is an amazing space of the long view. I think in the performances what was always kind of shocking to people is, yes, on one level, nothing happens, it’s a concert, but in fact it’s revelation after revelation. We’re so focused on the action movie, which has no revelation, but is just blowing up a lot of cars. If you’re interested in revelation, you have to get quiet. I think many theater people just imagine theater as making noise and as speaking fabulously, and not exactly as this quiet, revelatory space, and a space of memory. You imagine you’re living today as today, but you aren’t. You are actually living out yesterday. And it’s like, whoa, yesterday has not gone away at all, and there’s actually more of yesterday present today than there was yesterday. The weight of history actually intensifies rather than diminishes.

We spend a lot of our lives in conversations with people who are not in the room, and yet who are on our minds and in our hearts. To me those exchanges occupy a lot of our minds, every day. And we do carry these painful things in our hearts across a lifetime and into future lifetimes. Violence doesn’t just play itself out in one generation. And this violence against women, which is at historic levels right now, it’s been building across centuries and centuries and centuries, and so you just get the accumulation of it. In fact, something that was not addressed or acknowledged at the time just gets larger and larger over time and across generations.

So, that’s a little bit of the moral and psychic and spiritual venue of the performance. How do you set something in a space of moral reckoning, and memory, and some kind of hope, and some sense of failure, all intermingled? And then finally, that even people you really love turn out to have dark sides to them, and there are things you don’t want ever to tell anyone or know about someone else. I really pressed Toni to say, “Okay, now what is it that Othello has with Iago?” I mean, these guys hate each other, but they always have each other’s back. What is the weird bond that creates this super crazy, love-hate, mutually destructive pact that’s going on? And so, Toni, of course, created that amazing scene, a witness of the rape of the old women, and then Othello’s confession to Desdemona, which puts their relationship into a really charged place of, yes, her unconditional forgiveness, but also, the idea that the person you admire is also that. And so what is that space of feeling? It’s not exactly a living room. It’s a very private chamber that has no walls, is porous, and has these points of light and these points of darkness. So, that’s the stage picture.

So, having one actress who’s voicing all of these stories, is that a way of expressing how private these conversations are, and how hard it was for Othello to make the confessions that he does?

Yeah, and I think again, when you’re hearing a story, you want to know more about the storyteller. Why are they saying this? How did they learn this? What is their struggle with this material that they’re telling us, and how are they able to tell it and how are they not able to tell it, and what are they going to leave out, and what are they going to include? And so, in that way, storytelling itself is also a dramatic event that needs to be examined on many levels, and you need a sense that there are high stakes in how these stories are told, in what is underlined and what is erased. That is very much Toni’s project in a lot of her work, and Desdemona is no exception.

There was a panel discussion that I watched where you and Toni Morrison and Rokia Traoré talked a lot about the act of witnessing and how that is important within the space of Desdemona, but also within the theater at large. I was interested in what you said about the role that theater plays in helping whole communities come together and cope with tragedy. I think you described the act of witnessing in theater as a way to develop a collective conscience. I wanted to hear more from you on that idea, about how theater is both a medium and a space to help us cope with tragedy.

One of the most extraordinary nights of my life was when I was visiting friends in Bali, and we saw a traditional Balinese cremation ceremony. A lot of things that could never be acknowledged in public finally got said. There was also a lot of laughter about ridiculous secrets that everybody knew, but finally could say out loud. It was really overwhelming because these masked Topeng dancers would keep moving and then the voice would come out of them that was this woman whose body was lying there, finally speaking to the community, finally coming clean and giving the village the possibility to move on with a public acknowledgement of things that were never correct, or that now could be addressed. It made me think about how theater was invented primarily as a ritual for the dead. Most early forms of theater speak to the dead and invite the dead to speak to us, letting the dead know that we’re still thinking about them, and that we regret the way they left this world. We invite the dead to be with us again and to speak with us as honestly as possible. Those roots and origins of theater are in many, many cultures. So at its origin, theater is a space that’s meant to be occupied equally and visibly and audibly by the living and the dead, a space where something can be shared and expiated and recognized. And that recognition and that sense of a sacred truth is really what creates a community.

Both within Desdemona and also on a level of literature in general, there’s been some pushback against Shakespeare’s work (and works of the English canon) as not diverse, and a sense that we need to make space for stories from other places. That’s the reason I was really interested in reading Desdemona alongside Othello, because I feel like Morrison is making the argument that it’s still worth reading these older texts even though some have a problematic history. I just wanted to know if you had any thoughts on that, on how Morrison’s work functions as an adaptation of Shakespeare but also – not as a redemption of it exactly, but as an argument for why we should continue to engage with it?

I think the reason theater and literature were invented was to get beyond judgment and realize that the moral life of human beings is unbelievably complex. Yes, certain people do terrible things, and at the same time, are deep and valuable and beautiful human beings with so much to give. Everybody has to be welcomed and honored and treasured and cherished, and our work is to understand, not to judge. What is it like to understand ourselves, what is it like to understand each other, what is it like to understand the situation we find ourselves in? Literature opens up a space of understanding, and that was Toni’s incredible gift, to take difficult people who had very difficult lives, and to create a space of understanding, a space where suddenly, we’re sharing the life of somebody who is certainly not like you and certainly not how anyone would want to be, but it’s how they are. We want to blame this person, but in fact, their horrible action is a reflection of something much larger than themselves, a crisis that is so profound that it then creates these explosions of violence and further levels of victimization. There are very clear patterns. Can we please start to understand more deeply what’s happening so there can be more than just recrimination and rage in the aftermath? That way, we can start to prevent this violence ahead of time, and have responses that are not just too little too late, in which rage is substituted for some kind of positive, helpful, and liberating intervention.

Maddie Turner is a Rice alum (Class of 2021) who double majored in biochemistry and English,

with an English Concentration in Culture & Social Change.

Her senior seminar project in English involved conducting a comparative reading of Othello alongside Toni Morrison’s creative retelling of

Shakespeare’s play Desdemona, exploring the ways in which we can read canonical

English texts from a more critical perspective.

Since graduating, Maddie has been working as a

research assistant at MD Anderson studying pancreatic cancer. In her free time, she loves

cooking & baking, running, playing guitar and going to local concerts.