When we first reached out to Paige Quiñones to interview her about love poetry, her initial reaction was to say, “I don’t write about love.” Compared to more traditional love poets, Paige’s poetry definitely breaks the mold of what we normally think love poetry is. Instead of praising warmth and desire, her poems address a different side of love, exploring its deep anxieties. She draws on influences from confessional poets, like Anne Sexton, to push the boundaries of intimacy in her writing, and [to] expose the darker realities of falling in love.

Quiñones’ poetry gives the sensation of being chased—settled in the paranoia of being the hunter or the hunted. There’s a restless tension in some poems, a nervous stillness in others. Quiñones’ “Love Poem: Fox” feels dark, anxious, treacherous. Her “Still Life With Wadded Paper Towels” is conflicting, vulnerable, alternately pained and fondly perceptive. Quiñones’ “Aubade,” is bleaker, more elegiac, than the traditional form it adopts as its title—the speaker possesses an uneasy restraint. Her poetic range and interaction with traditional love poetry makes her an obvious candidate to understand, not only the relation between contemporary love poetry and its past, but also the future of the genre.

Paige Quiñones is an up-and-coming confessional poet in Houston. She is currently pursuing her PhD in poetry at the University of Houston, where she has also served as the managing editor of Gulf Coast and has recently been awarded the Inprint Donald Barthelme Prize in Poetry. Her work has appeared in Adroit Journal, Barrow Street Review, Copper Nickel, and elsewhere. We reached out to her, amid the pandemic, to conduct a virtual interview about love poetry, representation in literature, and her thoughts on poetic traditions. What follows is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

We listened to an interview that you did with Houston Public Media, and you mentioned that you were originally a pre-med student at the University of Florida before you decided to become a poet. What originally inspired you to pursue poetry, and who are your biggest influences?

So, I did my undergrad at University of Florida, and I went in with this idea that I would be double majoring in pre-med and in Spanish. And being pre-med was very hard on me. I think I just had these ideas about what I was supposed to become, influenced by [both] societal and family pressures. And I just happened to take a poetry class in the Honors College with—I don’t know if you’ve read any of his critical work—William Logan; you should read some of his criticism, it’s really mean. He’s an amazing professor because he loves his students as though they are his own children, as opposed to the people he lambasts in his reviews. I took a [poetry class in my sophomore year], and I just kept taking them, [meanwhile] pre-med was getting worse and worse. And I finally failed a class—like, I literally got an “F”. I was gradually realizing that it just wasn’t going to be for me. And so I was like, well, let me shift to more English-focused classes, and then suddenly, I was thriving.

Someone that I’m reading a lot right now is Anne Sexton, and looking at how she really changed the landscape of confessional poetry and broke a lot of boundaries in terms of form—if you’re reading any current poetry right now, almost all of it is confessional. [She was part of the movement that influenced] basically everybody who’s writing now who [break former conventions]—[who recognize] okay, we can write about ourselves, we can break our lines here, we can do that. We take that for granted, whereas she was [pioneering] that.

Early modern love poetry is [kind of] the opposite of what you’re describing: Very formal, very structured, [affirming] that there are certain things that qualify as poetry and certain things that don’t. How would you describe your understanding of traditional love poetry? Do you see your writing as responding to that?

I don’t gravitate towards formal poetry as much. I do think that there’s something to be said for knowing how to write formal poetry. By knowing how to do that, you will then write free verse better—it’s almost like knowing the rules before you can break them. And it’s useful to know how to write a sonnet, for example, but I generally tend toward free verse, maybe sort of loosely thinking about syllabic meter, not meter, but syllables per line.

I would say [one early modern poet I’m familiar with] is John Donne, and I love his poetry—I did a little lecture for my poetry students this semester on “Holy Sonnet 14”. “Holy Sonnet 14” [is] one of those poems that just gives me shivers every time I read it. Yes, it is a sonnet and it’s metrical and all this other stuff, but he’s doing such interesting machinations inside to get away with messing with the form a little bit. And it’s so homoerotically invested in God—it’s like, he wants to sleep with God. To me, that definitely gets away from this idea of courtly love and this very formulaic presentation of love on the page. When I think of love [I also] think of [poets] like Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz, [writer of] lesbian nun poems from Mexico—also [17th century].

In terms of my own writing, [for my Ph.D. exam, I’m currently thinking about] the politics of desire. What I’m beginning with is something that Anne Carson talks about in her book, Eros the Bittersweet—how the Greeks configured desire. And especially Sappho.

There’s this act of reaching towards something and wanting to hold something that can’t actually be held, like holding a block of ice, or holding a top while it’s spinning. And in my own poems lately, I have been writing about a man who has a hyperrealistic sex doll, and he’s in love. And I know it sounds kind of wacky. But I’m interested in what love looks like when it’s from one party to an inanimate object, and how the inanimate newness of it is changing with the advent of technology. Pretty soon we will have—if you’ve seen Ex Machina, for example—we’re going to have these androids and these [android] women who can theoretically develop some kind of a personality. So, it’s an interesting poetic exercise to think about love, not as between two people, but as between a person and something that is very close to a person.

What do you think the role of representation is in writing? How do you view the responsibility of representing certain identities? Do you find it freeing [or] limiting? Somewhere in between?

I would consider myself a confessional poet—I would be interested to see who doesn’t consider themselves confessional at this point. For myself, I exist between a lot of things. My father is Puerto Rican, but my mother is white. I spent some childhood in Puerto Rico, most of it in the U.S. mainland. I am bisexual. There’s this constant pulling and pushing in different directions.

I think [there’s] a challenge [posed particularly] for bisexual poets. You know, there’s always this assumption that bi women are actually interested in men and bi men are also actually interested in men. There’s this patriarchal idea, that everybody [is actually interested in men], which I think is pretty funny. I do think that I write in a mode that acknowledges [uncertainty]. And I’m kind of just claiming that middle point, as opposed to really feeling like I am some kind of authority on being something. I really don’t think I’m the authority on being anything.

The way you approach gender dynamics in your poetry is interesting, because what we’ve studied is mostly from the male point of view. Usually in these poems of desire, [the focus is on] male desire. How do you see yourself using your poetic voice to address this disparity?

I think that I am invested in critiquing hypermasculinity. I kind of like to think of it in these, like, maybe not explicitly Ovidian dynamics, but definitely working with it within mythological constructs of “pursuer” and “pursued” and “predator” and “prey,” and the violence that can happen in desire, especially masculine desire. I think that it’s kind of a scary aspect of my poems. I do find my poems a little bit scary. [But] that kind of masculinity is just going to [naturally] insert itself as a kind of antagonist in my poems.

And it’s interesting when [you] reached out to me to ask if I would do this interview, and [you were] talking about love poetry—I don’t write love.

But [actually] I think I do, and, more recently, [my poems have] entered into more positive territory. But at least in my book that’s coming out, [my poems exist in] a deep well of anxiety—this pursuit, the hunting, it’s all very kind of nightmarish for this speaker. And I think it’s interesting that love poetry can get there. It seems antithetical or wrong. But that’s what the majority of the love poems in that collection are doing.

That’s really interesting, because in early modern poetry, love is always idealized. It’s [presented as] your key to happiness. I found it kind of refreshing to read your poetry and see it in a different light and in a more, I guess you could say, nightmarish, but more realistic [way].

I think it accepts the anxieties, the humanity of [love]. If you look at the Greeks, the Greek poets were so afraid of falling in love because it wrecks you. We don’t stay sane in love. We’re crazy in love. We’re lovesick. We’re just kind of all over the place, completely mad. It’s an assault on your psyche and your whole entire mode of being to be in love. And they were terrified of that. And I think, with good reason.

We watched a video online of you doing a reading at the Contemporary Art[s] Museum [Houston] in honor of the 50th anniversary of Stonewall. One poem that really stuck with me was “To the Girl who Loves Girls,” particularly the last line: “No dreaming. No, you can’t dream yet.” That really stuck with me. How do you view the role of queerness in your poetry? How do you represent queerness and bisexuality through your description of relationships with men compared to relationships with women?

I did that reading [last year]. And I was commissioned to write the other poem that I read there, “Shotglass,” because I was the managing editor of Gulf Coast for the last two years, which is the UH graduate student literary magazine. For the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, we basically made a queer issue [where] we focused on queer artists, and we had a whole section of queer writers chosen by [Justin Torres]. And what I really liked about what he chose is that he basically compiled a list of a bunch of his friends, and they gave us writing that was in between poetry and prose, like in between drama and surrealism and realism. It was just kind of this amorphous collection of just great writing.

I think that I really like that writing doesn’t need a label. You don’t need to say “this is my bi poem.” It can just be weird, like shapeless or shapeshifting. And in that poem, “Poem for the Girl who Loves Girls,” a lot of my poems about women are kind of wistful in some way, or somewhat unrealized. I don’t have a ton of them, but if they are explicitly about women, it’s almost like Sappho, like watching the woman reaching for the apple. There is this kind of reaching toward but never really being able to fully grasp, as opposed to my poems about men, which are kind of just violent.

I think I’m writing more poems now that [move more toward gratifying love rather than reaching for it], at least the ones that aren’t in the sex doll realm. The ones that are kind of more confessional, more in the realm of my life, are getting away from that [unrealized version of love] because I’ve kind of exhausted that mode of writing.

And so, I’m now moving into more poems like “Aubade.” I see that poem as being a more traditional love poem and one that doesn’t necessarily end unsatisfactorily. It’s a little bit more positive. And I think it’s really hard to write a nice, sweet, good love poem. I think it’s important work to do. And I think that I’m kind of getting into that headspace, now more than I was before.

That’s interesting, because, talking about “Aubade,” it’s more of a traditional form. The premise is two lovers separating at dawn with the man leaving the woman, and there always seems to be a sense of longing. But, reading your poem, it feels very different from that traditional form. For example, your conceit in the poem was interesting: “longing is an improper bit at the mouth.” As you’re entering this next style of your writing, do you think that you circle back to the tradition of love poetry more? Is accessing the tradition more a way to extend your confessional poetry and your own concept of what love is?

Yeah, I think that’s great. I think you phrased it better than I could have. There’s only so much mining of trauma that I feel like I can physically do. And so then, you move on.

I think people become obsessed with different things at different stages in their lives. And I read some of the sections of poems that [your professor] sent me to look at, and I was so into them. For example, Robert Herrick’s “Upon Julia’s Clothes,” I love that one. Five years ago or so, I probably wouldn’t have felt that way. But, I feel something pulling me to return to a more formal idea of love poetry.

At the same time, I have the sex doll poems happening. Those are kind of messed up—deviant. It’s perverted in at least that section [of my book]. So, maybe, that’s why I’m interested in [those types of traditional poems]. I’d say, my confessional poems, they’re a little bit more standard love poems whereas the other ones are a bit wilder.

Would you say you see your confessional poems responding to a conventional style of poetry and emulating them, or do you think that they explicitly take expectations and subvert them?

I think it would depend on what we’re defining as conventional poetry. Here’s what I’ll say: I find a lot of poetry to be boring. We can’t really get away from that fact. Poems are exciting, especially once you put the work in. But sometimes, I find myself picking up the latest poetry magazine, and I’m maybe not willing to do that work.

What I’m doing with my poetry is that I always want to be “not boring.” And whether or not that’s successful, I don’t know. I think it’s sometimes inevitable that some poems are going to be boring. Nobody wants to admit that, but I think it’s okay to say that poetry is boring sometimes. I always want to write a poem that is on some level, lyrically, imagistically, or thematically exciting.

I do think some people tend to mask boring poetry with formal excitingness, like moving words across the page and doing all these wacky things, but when you look at those poems a little bit harder, it’s really just a boring form. And, I don’t want to do that. That’s really what I’m responding to. It’s also hard because, after working for the Gulf Coast for two years, [I realized that] doing editorial work can kind of bog you down. I was seeing so much poetry and reading things that are new, [but I kept on] seeing the same kind of poem over and over again. I think that’s the kind of convention that I really want to buck against. I don’t want to be writing a poem that’s following a similar kind of formula that everybody is publishing.

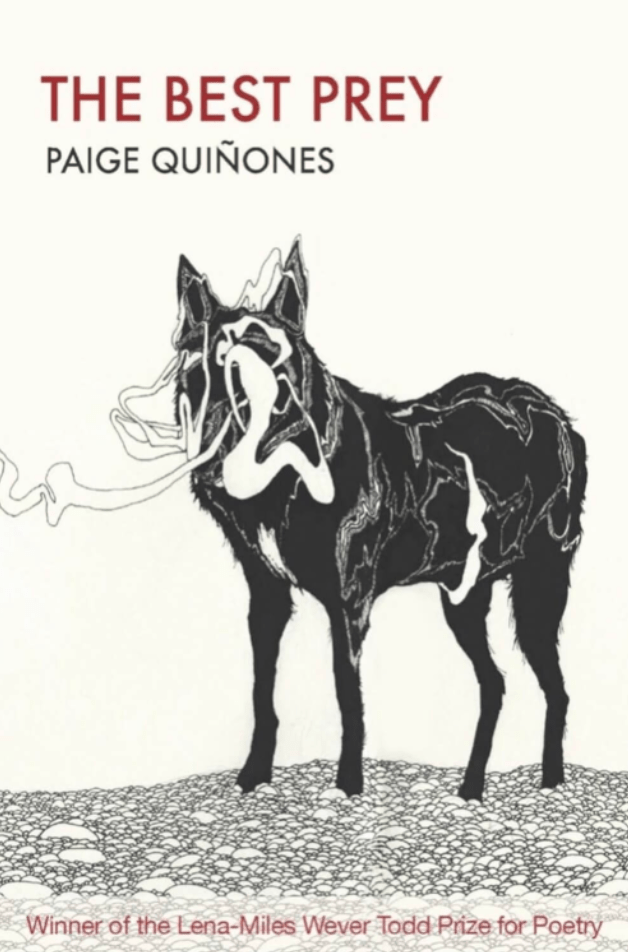

Earlier, you mentioned your book that’s coming out in February. Tell us more about that.

It’s very exciting! When they emailed me to let me know that my book won the manuscript prize, I came home and cried on the floor, and I was like “I can get a job!”

The book is called The Best Prey, and it’s very much an exploration of violent, doomed, desirous relationships. It stems from a deep well of anxiety. The pursuit, the hunting, it’s all very nightmarish for this speaker. It’s really about existing in between one space and another, and exploring the pain of not necessarily feeling connected to any one particular culture or identity. The speaker has to come to terms with a divorce and all this other conflict. There’s a lot of things happening. But I’m really looking forward to it, and I think it’ll be great.

Paige Quiñones is the author of The Best Prey, which received the 2020 Pleiades Press Lena Miles-Wever Todd Prize for Poetry. She has received awards and fellowships from the Center for Mexican-American Studies, the Academy of American Poets, and Inprint Houston. Her work has appeared in Best New Poets, Copper Nickel, Crazyhorse, Juked, Lam

Aaron Nguyen is a senior at Rice University double majoring in English and Biosciences. His literary interests include works in the medical humanities as well as the Asian American diaspora. In his spare time, Aaron likes to crochet beanies, watch Survivor, and submit entries to the weekly New Yorker cartoon caption contest.